Biblioterapia para prevenir el acoso. Una revisión sistemática

Bibliotherapy to prevent bullying. A systematic review

Nuria Anaya-Reig

Universidad Rey Juan Carlos

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3766-0761

Carlota Martín-Borja Gallego

Universidad Rey Juan Carlos

https://orcid.org/0009-0001-6236-3590

Vicente Calvo Fernández

Universidad Rey Juan Carlos

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7620-9420

vicente.calvo.fernandez@urjc.es

Juan Calderón Cisneros

Universidad Estatal de Milagro

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8167-8694

RESUMEN

El acoso escolar constituye un grave problema social y sanitario por las dimensiones que alcanza y las consecuencias que conlleva. Puesto que se ha demostrado que la aplicación de la biblioterapia en intervenciones sociosanitarias pediátricas y educativas resulta eficaz, cabe suponer que también puede usarse como herramienta de prevención del acoso escolar. En este trabajo se presenta una revisión sistemática de estudios sobre el uso de libros de lectura contra el acoso escolar. Para llevar a cabo la revisión se realizó una búsqueda, sin restricción de idioma, fechas o bases de datos, a través del Buscador de Recursos para el Aprendizaje y la Investigación de la Universidad Rey Juan Carlos de Madrid (BRAIN). 12 de los 2.604 registros identificados inicialmente cumplieron los criterios de búsqueda, selección e inclusión establecidos. En este artículo, se analizan estos 12 trabajos. Los datos que se extraen del análisis permiten confirmar la validez y utilidad de la biblioterapia para ayudar a prevenir y abordar el acoso escolar.

PALABRAS CLAVE

Bullying; adolescence; bibliotherapy; Reading; prevention.

ABSTRACT

Bullying is a serious social and health problem due to the dimensions it reaches and the consequences it entails. Since the application of bibliotherapy in pediatric and educational social-health interventions has been shown to be effective, it can be assumed that it can also be used as a bullying prevention tool. This paper presents a systematic review of studies on the use of reading books against bullying. In order to carry out the review, a search was conducted, without restriction of language, dates or databases, through BRAIN (acronym in Spanish for Learning and Research Resource Finder) of the King Juan Carlos University of Madrid. Twelve of the 2,604 records initially identified met the established search, selection and inclusion criteria. In this article, these 12 papers are analyzed. The data extracted from the analysis allow us to confirm the validity and usefulness of bibliotherapy to help prevent and address bullying.

KEYWORDS

Bullying; adolescence; bibliotherapy; reading; prevention.

1. INTRODUCTION

According to UNESCO (2021), from the Global School-based Student Health Survey (GSHS) and Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC), one in three students is a victim of bullying. The data also reveal that 25 % of students have been bullied in Europe and 31.7 % in North America. In Spain, in accordance with data collected by the OECD, 17 % of students aged 15 have been victims of bullying (Spanish Ministry of Education and Vocational Training, 2021). It has also been found that both boys and girls aged 10-14 are more likely to be bullied (Amnistía Internacional, 2019).

Moreover, victims of bullying are known to be up to four times more likely to suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder or severe anxiety and up to five times more likely to have suicidal ideation (Armero Pedreira et al., 2011). Moreover, in schools where bullying is prevalent, academic outcomes are significantly lower (Amnistía Internacional, 2019).

Given the scale of this phenomenon and the serious negative consequences it entails, it is urgent to do everything possible to try to curb and prevent it. In this regard, it has been pointed out that prevention should start at the primary level (Sastre, 2016). Moreover, this is the best intervention (Armero Pedreira et al., 2011). Taking into account the nature of the problem, it can even be said that preventive work serves to help detect and tackle it when it appears.

Can bibliotherapy help in such preventive work? Given the benefits of bibliotherapy in pediatric health care, both in the educational and hospital settings (Anaya-Reig, 2022), it seems reasonable to think so and to ask to what extent it has been used for this purpose and what results have been obtained. The aim of this paper is to answer these questions through a systematic review of the use of bibliotherapy to combat bullying. More specifically, it aims to: 1) collect studies that have used bibliotherapy to tackle bullying, and 2) study the extent to which preventive bibliotherapy has been effective in reducing bullying.

Importance of systematic reviews.

Despite their great lack of knowledge among the school community, systematic reviews are of great value for the systematization of scientific knowledge, also in the field of education (Sánchez Martín et al., 2022).

Although their birth took place as a result of the so-called controlled clinical trials with therapeutic interventions (Villasís-Keever et al., 2020), they have now opened up their field and consist essentially of the systematic investigation of original primary studies on a given problem in order to synthesize the results (Ferreira González et al., 2011).

Considered by the scientific community as the highest level of evidence, especially those based on empirical studies, they are a valuable tool for improving research (Sánchez-Meca & Botella, 2010). They are fundamental for increasing the validity of the conclusions of individual studies and help to identify areas of uncertainty for further research (Ferreira González et al., 2011). In addition, they are a great time-saver in research, as due to technological advances and easy access to the internet, specialized publications have multiplied exponentially (Selfa & Falguera, 2021).

A brief approach to bibliotherapy.

Although the healing function of reading dates back to antiquity (Castro & Altamirano, 2016), the term bibliotherapy was coined in 1916 by Samuel Crothers (Heath et al., 2005) and the first medical references to its use date from the 1930s (Proyecto Biblioterapia, 2018), its use today is still very uneven depending on the countries and fields of application. In this sense, it is very illustrative that the Anglo-Saxon culture, one of the most experienced in this discipline, has included the definition of the term in its dictionaries for two decades (Ouknin, 1994), while countries such as Spain and France have not yet registered it.

It has been pointed out that its therapeutic effect has to do with its capacity to help face adverse situations such as illness, either because it favors identification with characters, or because it constitutes a support for overcoming them, or as an element of accompaniment (Hidalgo & Cantabrana, 2017). In addition, the healing capacity of literature is possible thanks to the fact that the reader, conveniently guided through dialogue, pays close attention to the thoughts, conversations and problems of the characters. This makes it easier for them to associate certain situations in the fiction with their reality and, in this way, to sympathize with the characters and reconsider various solutions similar to those in the book that can be useful in resolving conflicts in their day-to-day lives (Trent & Richards, 2018).

Heath et al. (2005) refers to five stages the person goes through in their healing process. The main stage is engagement, whereby the narrative being read, in accordance with the plot presented in the book, arouses interest and intrigue. The second stage is identification with the characters, which is stronger the more similar they are in age, personality and situations in which they are immersed. The next stage is the so-called “catharsis”, which consists of the emotions that are released as the character overcomes the obstacles along the way with which the reader has previously identified. In the fourth phase, “insight”, the reader reflects on the event in the book and its corresponding solution. When the reader realizes that the seemingly unsolvable difficulty in fiction has been successfully overcome, he or she regains hope for a solution to his/her problems. He/she then looks for a plausible applicability in his/her real environment. Finally, in universalism it is realized that not only the reader himself/herself endures and suffers from internal struggles, but that all those around him/her also experience and even share them. In this way, he/she begins to feel that he/she is in a safe space to free himself/herself, can discuss his/her inner conflicts and acquire adequate conflict resolution skills.

Types or uses of bibliotherapy.

Although there is no unanimous classification of the different types of bibliotherapy, the following taxonomy can be considered:

•Rehabilitative vs. clinical (Naranjo Mora et al., 2017): rehabilitative bibliotherapy constitutes a tool for coping with the disease and adapting to its evolution. It can be carried out, in groups or individually, by librarians or health professionals. Clinical bibliotherapy is used with patients with mental, emotional or physical illnesses and is subject to medical prescription as a complement to established treatment. Castro Santana and Altamirano Bustamante (2016) comment that its effectiveness is determined by methodological studies and establish the following category.

•Creative or literary therapy: this involves reading literary works in search of help. In this regard, it has been pointed out that poetry, novels and autobiographies are particularly suitable genres to alleviate the suffering derived from an illness (Hidalgo & Cantabrana, 2017).

•Educational or personality development (Sevinç, 2019): is that which aims to redirect inappropriate behavior, help coexistence or prevent emotional problems. In this type of bibliotherapy, it is imperative to foster empathy and encourage the resolution of personal problems in order to help people develop coping skills.

2. METHOD

Search and selection strategy.

With the aim to guide the search, the specific research question was firstly defined: What has bibliotherapy been used for and has it been effective as a tool to deal with bullying in schools with a child and youth population? It was established on the basis of the so-called PICO format (Navarro Mateu & Martín García-Sancho, 2007; Sánchez Martín et al., 2022):

(P) Population: young people aged 6 to 21 years inclusive or their parents,

(I) Intervention: bibliotherapy in the educational setting,

(C) Comparison: other possible intervention group(s) or control group(s),

(O) Outcome(s): results obtained.

Then, in January 2023, through the BRAIN search engine (acronym in Spanish for Búsqueda de Recursos para el Aprendizaje e Investigación, i.e. Searching for Learning and Research Resources) of the King Juan Carlos University, the whole process of searching and selecting the records was carried out.

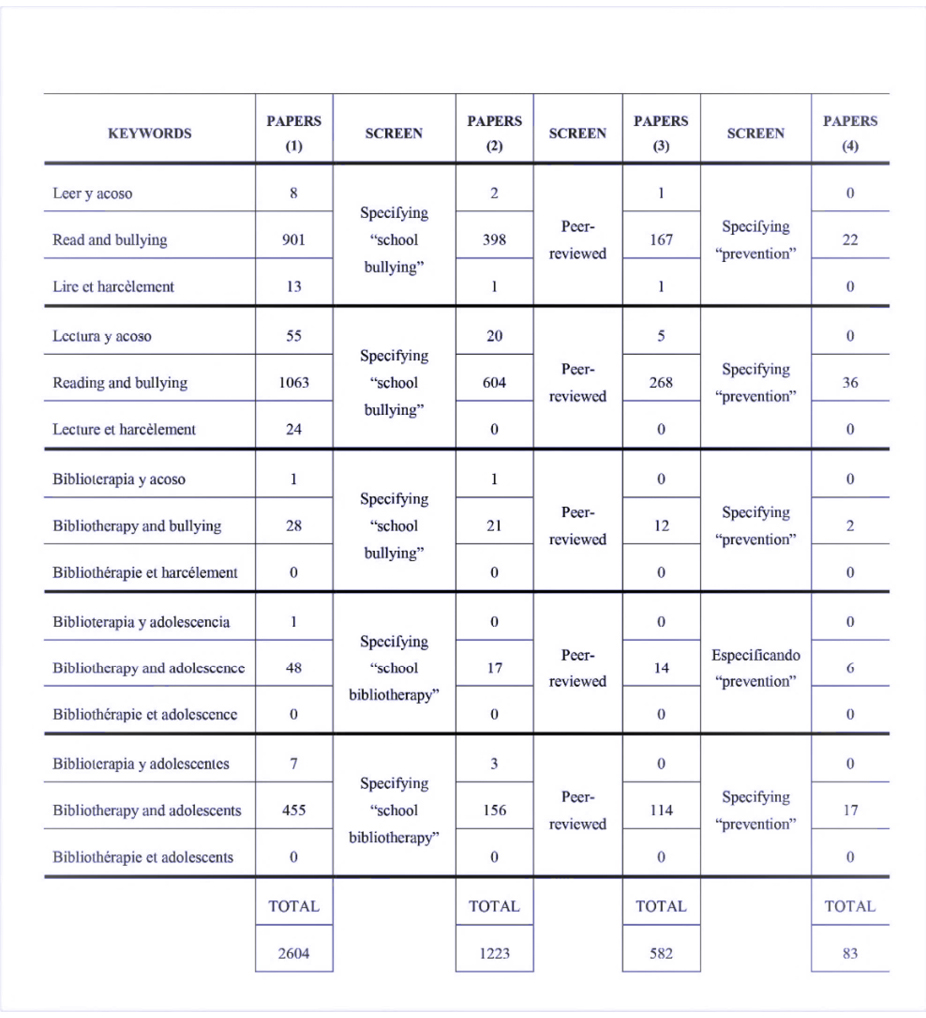

In the initial general search, the following pairs of terms in English, Spanish, and French were used as keywords: “reading and bullying”, “reading and bullying”, “bibliotherapy and bullying”, “bibliotherapy and bullying”, “bibliotherapy and adolescence” and “bibliotherapy and adolescents”. There was no language or year restriction and, to ensure that as many papers as possible could be located, the system was set up for extended crawling in all cases. A total of 2,604 studies were found.

The search was then refined by adding the term “school” to the above keywords in the three languages mentioned, and only papers on school bullying (as opposed to workplace bullying) and bibliotherapy in education were selected, resulting in a total of 1,223 records, of which only those peer-reviewed were taken, 582. Finally, the search was narrowed to the subject “prevention” and left 83 publications for review, of which 18 were eliminated as duplicates, making 65, all in English. Figure 1 shows the details of the search and selection procedure.

Figure 1. Keywords, screens and results of the procedure

Source: Own elaboration

Data collection and analysis

Of the 65 papers selected, titles and abstracts were read to determine whether they met the following inclusion criteria: a) studies on the use of books for bullying prevention, b) population aged between 6 and 21 years, and c) studies related to the educational field. Given that some papers referred to a different academic level than the one in Spain, in order to be able to apply the age-related criterion, the correspondence of their educational system with the Spanish one was established with the help of Relocate Global (2022) (see Table 1).

Table 1. Correspondence of academic levels between Spain, USA and UK.

|

Course in Spain |

Course in USA |

Course in UK |

Age of students |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1.º de Educación Primaria |

Grade 1 |

Year 2 |

6-7 years |

|

2.º de Educación Primaria |

Grade 2 |

Year 3 |

7-8 years |

|

3.º de Educación Primaria |

Grade 3 |

Year 4 |

8-9 years |

|

4.º de Educación Primaria |

Grade 4 |

Year 5 |

9-10 years |

|

5.º de Educación Primaria |

Grade 5 |

Year 6 |

10-11 years |

|

6.º de Educación Primaria |

Grade 6 |

Year 7 |

11-12 years |

|

1.º de Educación Secundaria |

Grade 7 |

Year 8 |

12-13 years |

|

2.º de Educación Secundaria |

Grade 8 |

Year 9 |

13-14 years |

|

3.º de Educación Secundaria |

Grade 9 |

Year 10 |

14-15 years |

|

4.º de Educación Secundaria |

Grade 10 |

Year 11 |

15-16 years |

|

1.º de Bachillerato |

Grade 11 |

Year 12 |

16-17 years |

|

2.º de Bachillerato |

Grade 12 |

Year 13 |

17-18 years |

Source: Own elaboration

The variables to be analyzed, according to the PICO format, were: a) sample characteristics, b) educational context of application, c) comparison with other interventions, and d) results obtained with the intervention.

3. RESULTS

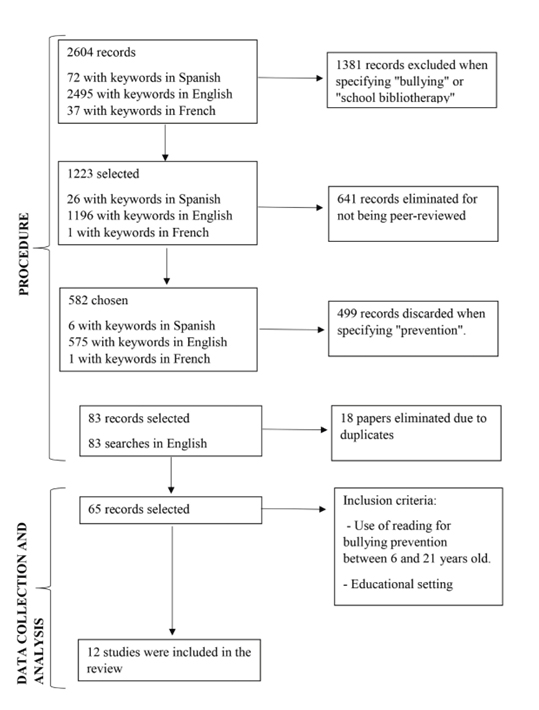

12 papers were found on the use of bibliotherapy to prevent bullying in educational settings. Details of each can be found in Table 2. The flow chart (Figure 2) provides a summary of the entire search and selection process.

Figure 2. Flowchart from PRISMA 2020 (Page et al., 2021).

Source: Own elaboration

Table 2. Enumeration and description of the compiled works.

|

ID / Study |

Scope / Subject / Duration |

Sample (size, age and type) |

Implementation and materials |

Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

#1 Korneliussen (2012) |

Capstone Project. Subject: English Language and Literature. Course 2010/11. |

n = 65. Age: 13-14. Gender: NC. Students Grade 8 Fairview. 95 % African American. |

CSS / Individualized reading of excerpts from Warriors don’t Cry, and open activities (research work, brainstorming, written reflection on historical images and visit to the place where it happened, presentation of results to the rest of the school and play about the event). |

Raising awareness among pupils through empathy, encouraging action for its eradication. Promotion of reading among pupils. |

|

#2 Pytash (2013) |

Public university in the Midwest. Subject: Teaching Reading with Literature, within Integrated Language Arts Program. One semester. |

n = 22. Age: 19-23. Gender: –21 female. –1 male. Students in the last year of the program. |

Active participation from reading by telling about one’s own experiences and about the mark it leaves on one. Reading a book of personal choice or Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher or Hate List by Jennifer Brown and participating in open activities and structured or semi-structured interviews (online literature circles, exchange of messages according to one’s role, interviews about why the book was chosen and about the learning extracted for their future teaching practice). |

The readings helped future teachers to learn about bullying (types, how to act, etc.) and suicide (warning signs), and to reflect on this decision made by some of their friends. It encouraged them to design a safe teaching environment and to imagine how they would have acted. |

|

#3 Shelton (2017) |

Rural and conservative southeastern US environment. Subject: English Literature. |

n = NS. Age: 14-18. Gender: NS. 100 % socially deprived. 70 % students of color. |

CSS / Reading of an article by a local activist and The Merchant of Venice. Open and closed activities (discussions on race, gender, ethnicity, religion, homophobia, sexism and objectification of women). |

Reflection and questioning of stereotypes and racial, ethnic, religious, etc. discrimination. Reduced use of less offensive vocabulary and encouraged others to do so. |

|

#4 Ansbach (2012) |

Manchester, NH, Township High School. Subject: General English. One week: “New Jersey Respect Week”. |

n = 100. Age: 16-17. Gender: NS. Grade 11 students. |

CSS / Jenna Russell’s essay “A World of Misery Left by Bullying” and Dear Bully: 70 Authors Tell Their Stories, an anthology of essays. Open and closed-ended activities (documenting ideas from readings with guided questions and sharing in pairs, groups and with the rest of the class, creating posters and writing reflecting emotions in the voice of one of the bullying constituents, summarizing the essay read crafting a hopeful message). |

Students developed cognitive and affective empathy and considered their role in bullying. Increased interest in the topic to know how to offer comfort and support to victims. Improved enjoyment of Reading. |

|

#5 Quinn et al. (2003) |

Urban and suburban areas of Philadelphia. Summer Clinical Reading Program. 5 weeks. |

n = 24. Age: 10-15. Gender: mixed. 24 children from 3 classes in 5th- 9th grade. 25 % Asian Amer. 12.5 % African Amer. 62.5 % Caucasian. |

CSS / Reading of Crash by Jerry Spinelli and a variety of open and closed-ended activities (e.g., summary, reflective journals, questions about a particular character or theme, Theatrical performances of excerpts from Crash, completing possible thoughts of the protagonist). Use of Venn diagram to compare characters or events. After the reading, design of T-shirts with anti-bullying slogans and activity to distinguish negative and positive comments. |

The intervention raised awareness and helped students to learn about perceptions and to discover that they had preconceived ideas about bullying and even to recognize having had similar attitudes to the bullies in some situation and wanting to change it. It also promoted respect for diversity of opinions and empathy and encouraged reading. |

|

#6 Chisholm & Trent (2012) |

Appalachian High School. Approx. 15 days. |

n = 27. Age: 15-16. Gender: –6 female. –21 male. High percentage of students in low-cost lunch. |

CSS/ Questions before and after reading about what bullying is and beliefs about the main characters. Reading aloud of Thirteen Reasons Why: comprehension and interpretation. Instructional activities to delve into causes and consequences of bullying and suicide (reflection on alternative decisions, learning and symbolism; causal chain; mural to connect fiction with reality; and periodic literature circles on life implications). |

The students reflected on their own role in protecting the feelings of others and preventing bullying in their own lives. With the chain, they realized the weight that Hannah was bearing. The survey showed no significant changes in responses before and after the intervention. |

|

#7 Johnson, Augustus & Agiro (2012) |

Advanced Language Arts. |

n = NS (a school class). Age: 14-15. Gender: NS. |

CSS/ Reflection on media manipulation based on Heidi Cody’s American Alphabet and the representation offered by the media according to Jean Kilbourne. Reflection on conflicts in the media based on a survey. Reading of key excerpts from Shakespeare’s Othello (Julius Lester) and viewing of film scenes (Laurence Fishburne and Eamonn Walker). Socratic seminar: how can we protect others and ourselves from violent and harmful actions? Final project: consider a solution to a current problem by creating a positive message. |

Verification of the damage that can be done by verbal or media manipulation in stereotypes and social pressure, which can end in harassment. Sharing of strategies to avoid conflicts: emotional control, prioritizing help and support to others or being kind. Recognition that Youtube and Facebook empower the bully and incite hatred by collecting and publicizing violence. The majority of posters created were against verbal harassment or social pressure. |

|

#8 Wang et al. (2015) |

Southern California. Bullying Literature Project. 5 sessions of 35-45 min. in 5 weeks. |

n = 141. –EG = 78. –CG = 63. Age: 8-10. Gender: –48.8 % female. –57.2 % male. Students (60 % Hispanic amer. 50 % in low-cost lunch program). |

Teacher training Quasi-experimental research with pre-post evaluation. Psychologists, teachers and counselors read children’s literature stories with students discuss and act out possible bullying situations. |

The program was effective in activating students emotionally and improving their prosocial behavior. There were no significant changes in terms of bullying or victimization. |

|

#9 Selkie et al. (2018) |

Annual convention for videobloggers. For a single day. |

n = 67. Age: 14-18. Gender: –91 % female. –9 % male. Teenagers interested in vlogging. |

CSS/ Paper form on possible actions to prevent or address electronic bullying based on a vignette describing a cyberbullying situation. Anonymous surveys. |

Participants formulated ways to address cyberbullying with and without the use of technology. They also valued the bystander as an effective support agent for the victim, referring strategies in this regard. |

|

#10 McCann et al. (2012) |

Elementary Education. |

n = 24 Age: NS Gender: NS Upper level students. |

CSS/ Intervention in groups. Writing and representation in groups of 4 students of a script about bullying, where the bully improves behavior, with the aim of sensitizing lower grades. Debate on conflict resolution based on a practical case. |

The shyer students and, in some cases, victims of bullying, dared to take a role in the performance. General agreement in the discussions: all agreed that there should be a sincere apology, not one forced by an adult. Moreover, some added that there should be some token to repair the damage done and show remorse. |

|

#11 McCarty et al. (2016) |

AC4P Program (Actively Caring for People). 6 consecutive Fridays. |

n = 404. Age: 7-12. –Grade 2= 107 –Grade 3= 100. –Grade 4= 54. –Grade 5= 89 –Grade 6= 54. Gender: NS. Students –77 % Caucasian. –1 % African Amer. –4 % Hispanic-Amer. –18 % Asian. –0.9 % in low-cost lunch. |

CSS/ Teacher training. Assessment of students on self-esteem and number of bullying situations witnessed with weekly surveys. Writing by students about stories related to prosocial behaviors observed in others or in themselves. Reading several at the beginning of each class, and choosing one, whose participants (observer and interpreter) are rewarded with an Actively Caring for People bracelet to wear throughout the day as “caring heroes”. Discussions in random pairs to get to know each other (what they wanted to do, talents, fears...). |

Increased self-esteem and prosocial behavior. Reduction in the number of bullied and harassers per week. |

|

#12 Smith et al. (1999) |

Elementary education in two Midwest schools (Topeka and Kansas). Gentle Warriors Program. Several months. |

n = +25. Age: NS. Gender: NS. Students. |

CSS / Meeting with children and teachers to raise awareness about bullying with role-plays and posters throughout the school. Workshops for parents. Children: non-physical ways to avoid conflict Gentle Arts (coping techniques and philosophies, meditation and self-control; strategies to strengthen their self-confidence). Sensei reads classics and books and stories related to The Bushido Code (respect for others and empathy). Peer leadership program with adult mentors among teenagers at a local high school and they both had self-discipline problems. Each student helps with homework and talks to one child. Evaluation by interviewing 25 random children (6 bullies, 5 victims, 5 bystanders). |

The children showed great interest in the reading activity by Sensei and showed amazing self-control while reading. In addition, they learned to deal with interpersonal conflicts and their self-esteem improved. The rate of expulsions and visits to the principal decreased. Academic achievement tests and the learning environment improved. |

|

CSS= Cross-sectional Study / NS= Not stated / EG= Experimental group / CG= Control group |

Source: Own elaboration

Sample.

The studies reviewed included 899 subjects, although several of them do not specify the sample size. Although most of them do not explicitly state the age of the participants, the academic level they were studying (second-grade, third graders and fourth graders, fifth and sixth-grade, eleventh-grade, grades 5 through 9 and eighth grade), so that the subjects ranged in age from 7 to 23 years. Overall, this was a multicultural sample, often from disadvantaged socioeconomic classes. All participants lived in the United States: California, Midwest, rural-conservative southeastern United States, Manchester (Hillsborough), northeastern Virginia, urban and suburban Philadelphia, Appalachia, and Seattle.

Educational context of application.

All the interventions were carried out in secondary school or university classrooms, except for one that took place at a convention for videobloggers. They were developed either as dynamics of a school project to prevent bullying in the classroom (Actively Caring for People Program, Capstone Project, Clinical Reading Program or Bullying Literature Project) or as crosscutting activities within subjects related to English Language and Literature (Advanced Language Arts, Teaching Reading with Literature, General English and English Education).

Texts used.

The readings used in the various interventions were:

Warriors don’t Cry, by Melba Pattillo Beals (Pocket Books, 1994). Based on true events, the book tells the story of the Little Rock Nine, African-American students including the author, and the integration and experiences they had at Little Rock Central High School in 1957. When they arrived at the school with a scholarship for their good school performance, they received a dismal reception from their classmates and teachers, who spat at them, insulted them, kicked them, threw stones at them and poured acid on them, arguing the difference in their skin color. Although it is true that occasionally some students tried to help the nine, the rest of the educational community participated in the harassment, either directly with psychological or physical intimidation, or indirectly, as spectators.

Thirteen Reasons Why, by Jay Asher (Razorbill, 2011) is about Hannah Baker and the possible reasons for her suicide. Before she dies, Hannah records her voice on thirteen cassette tapes, naming each one after one of her classmates. In them, she narrates a series of events closely linked to the bullying she suffered at the hands of each of those students.

The Hate List, by Jennifer Brown (Little Brown, 2009) is about engaged couple Valerie and Nick, who were constantly bullied by their classmates until they decided to make a hate list. One morning, Valerie learns that her boyfriend has caused the death of several of the high school students whose names were on the list they had created together. She manages to save one of the students and, as a result, the police absolve her of all guilt, against the opinion of her family, the faculty and other students.

Dear Bully: 70 Authors Tell Their Stories, an anthology of essays compiled by Megan Kelley Hall and Carrie Jones (Harper, 2011). Aside from this core reading, from which students in the group where it was applied read only excerpts, Jenna Russell’s article “A World of Misery Left by Bullying” from the Boston Globe was used, which chronicles the harrowing and painful years of bullying in adults now in their 30s and 60s.

Crash, by Jerry Spinelli (Laurel-Leaf Books, 2004): the plot revolves around the book’s title character, Crash, who has known Penn Webb since the age of 7 and who is subjected to constant and escalating bullying. Only when Crash’s grandfather, Scooter, intervenes does the protagonist reflect and change his attitude towards Penn.

The Merchant of Venice, by William Shakespeare. Bassanio urges his friend Antonio to provide him with a loan that will allow him to surprise Portia, a wealthy heiress, and marry her.

Othello, by William Shakespeare. Othello, governor of Cyprus, receives Desdemona, the daughter of a wealthy Venetian, as his wife. Interceding in their love story is Iago, who persuasively and mischievously makes Othello believe that his wife is being unfaithful. Othello, complexed by the colour of his skin, does not doubt Iago’s words to the point of killing his wife. Emilia, after Desdemona’s death, reveals Iago’s perverse actions.

The Bushido Code, by Nitobe Inazo, about the moral code and values of the samurai.

In summary: except for the last three, all the books chosen to carry out bibliotherapy in the classrooms dealt with stories directly related to bullying. The works that did not do so expressly did do so indirectly and the teachers made the final teaching explicit. On other occasions, the students themselves create the stories and they are read in class (McCann et al., 2012; McCarty et al., 2016).

Implementation of interventions.

All interventions were aimed at raising awareness and helping to prevent bullying among students or teachers. In some cases, the aim was also to help detect and eradicate it. The people who carried them out were mainly teachers. To this end, they provided the participants with books or excerpts from books. The most common specific topics dealt with were school bullying due to gender differences towards women, race or homophobia. The duration of the intervention varied from one day to the whole school year.

The work dynamics usually revolved around three moments with respect to the reading of the chosen material: before, during and after reading. Those tasks that preceded the reading of the chosen book or fragment were of an investigative and reflective nature and involved, depending on the work, other readings (digital or on paper) and the use of images and/or videos. Regarding the reading moment, it should be noted that it was carried out individually and included the annotation or underlining of important ideas for a brainstorming that would take place afterwards. This brainstorming was carried out with the class as a whole or in small groups and, on many occasions, generated discussions among the students. In some cases, in addition, literary circles were set up for group work, individual or group writing of literary texts (haikus, letters, narratives, etc.) was used, or interviews, theatrical performances or other awareness-raising dynamics were carried out.

The evaluation of the effectiveness of the interventions, which was carried out in all cases through teacher observation both during and after implementation, shows the effectiveness of the process. For example, one of the papers refers how, when a conflict of considerable severity occurred after the Capstone Project, one student stopped being a bystander and intervened, reminding his classmates of the consequences their actions would cause if they continued (Korneliussen, 2012). One day after finishing awareness classes with William Shakespeare, one of the students criticized another student’s T-shirt, attributing sexist and homophobic overtones to his opinion, to which a girl reacted by encouraging her classmate to watch his words to avoid generating unrest among the collective (Shelton, 2017). A boy who found an explicit bullying situation from Crash to Penn funny, laughed upon reading it, but upon acting it out commented motu proprio that Crash should have received a punishment (Quinn et al., 2003). On the other hand, one of students expressed to his peers his desire to create a safe environment for his future learners (Pytash, 2013). In addition, three interventions included a final outreach activity about what they had learned in order to raise awareness of the problem to the rest of the high schools with displays (Korneliussen, 2012) or posters (Ansbach, 2012; Johnson et al., 2012), and in others interviews were conducted (Pytash, 2013; Smith et al., 1999).

Results of interventions.

The studies reviewed show that in general the interventions were effective in the educational setting in combating bullying, both in childhood (6-12 years), adolescence (13-17 years) and early adulthood (18-23 years). More concretely, it can be said that they proved useful to:

Promote empathy in the different agents involved and foster healthy and safe interpersonal bonds among the educational community.

Prevent the formation of prejudices, as well as negative stereotypes and discrimination.

To promote respect for diversity.

Raise students’ awareness of bullying and improve their training on how to deal with it, how to help victims and learn conflict resolution.

To improve students’ self-esteem.

Contribute to teacher training in the detection of signs of bullying and suicide.

In addition, another additional advantage that studies on this way of working show is that, in some cases, it contributes to promote reading habits.

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The present review allows us to conclude that bibliotherapy is a very useful tool for bullying prevention. In particular, it should be noted that its ability to promote empathy in cases of bullying is consistent with the fact that the promotion of empathy is one of the general benefits of reading (Alonso Arévalo, 2022). And the same can be said regarding the improvement of conflict resolution skills in the school context: it is in line with its ability to develop coping skills (Studer & Mynatt, 2015), with that reading fiction improves Theory of Mind (Kidd & Castaño, 2013) and with the fact that reading stories about others activates the neural networks involved in ToM (Mar, 2011). This is especially noteworthy, moreover, because awakening empathy is paramount to prevent bullying, given that bullies show very low empathy and are unable to put themselves in the place of their victims (Nolasco Hernández, 2012).

Another relevant aspect of the results is the potential of bibliotherapy to improve teacher training on bullying, since a substantial part of this problem continues to be the lack of knowledge of action protocols on the part of the agents involved. Beyond these results, it is worth highlighting a positive element of bibliotherapy: its low cost (Anaya-Reig, 2022), which can facilitate a wide application at an institutional level and in a general scope, not limited to certain centers. It is important to highlight these two variables, because it has been found that: a) teacher training in violence and bullying is one of the factors present in those countries that have managed to reduce or maintain low levels of bullying, and b) the implementation of small-scale programs (only in some centers or only to some teachers) is a factor that limits the effectiveness of interventions (UNESCO, 2021).

Therefore, in relation to the above, it is also appropriate to emphasize our full agreement with Cañamares Torrijos and Navarro Olivas (2015), who, in a paper on the selection of books to prevent bullying, assessed that bibliotherapy, as a useful element to generate a good, safe and inclusive environment in classrooms, should be a mandatory tool to address bullying. Previously, in this same line, Heath et al. (2011), recommended bibliotherapy to address bullying in primary classrooms.

In light of the results, it also becomes clear that, although bibliotherapy is a type of intervention that is easy to apply (Jones et al., 2021), it is a relatively little used tool, especially in Latin America, as shown by the fact that none of the studies included in this review have been carried out there. In Spain, for example, the term itself is still in the recognition period or that only 12 studies have met the search, selection and inclusion criteria of this review for in-depth reading and data extraction, although some authors have suggested, without using the term bibliotherapy, similar strategies to prevent bullying, such as the use of digital comics (Cáceres-Reche et al., 2022).

In summary, it can be concluded that, given the potential benefits that can be obtained with the use of bibliotherapy to help deal with bullying, it is convenient to promote its knowledge, training and application among different education professionals, as well as research in this field. The same parameters established in this review can serve as a guide to promote the latter work. There is a lack of controlled studies, published in specialized journals that require methodological systematicity for their publication and that are peer-reviewed. It is of particular interest to continue investigating to what extent and under what conditions bibliotherapy is effective in educational contexts through the systematic application of interventions that include, if possible, large samples and control groups.

Finally, it is necessary to point out the need for systematic reviews to remedy the limitations of these studies (in terms of the age included in the sample, the search platform or the selection filters) and which have left out very interesting studies developed with younger children or which can only be located by resorting to other sources (for example, academic platforms such as Researchgate or Academia) and which, nevertheless, also shed light. Thus, for example, Spencer (2013), whose study with first graders who were taught specific anti-bullying skills through didactic instruction or bibliotherapy, showed that in both cases, compared to a control group, students achieved a greater understanding of bullying, used a broader vocabulary about bullying, and demonstrated more specific and varied actions in response. It is just one indicator of how future reviews may provide valuable materials for research and socio-educational interventions in this area.

REFERENCES

(2022). Biblioterapia: la lectura como fuente de placer y de bienestar. In E. M. Ramírez Leiva (Coord.), Los poderes de la lectura por placer (pp. 49-59). UNAM. Instituto de Investigaciones Bibliotecológicas y de la Información.

Amnistía Internacional (2019). Hacer la vista… ¡gorda! El acoso escolar en España, un asunto de derechos humanos. Amnistía Internacional.

(2022). Uso de la lectura en la atención sanitaria pediátrica: una revisión sistemática. In M. M. Molero Jurado, M. M. Simón Márquez, P. Molina Moreno, A. B. Barragán Martín, Á. Martos Martínez & J. J. Gázquez Linares (Comps.), Investigación y práctica en contextos clínicos y de la salud (pp. 187-195). Dykinson.

(2012). Long-Term Effects of Bullying: Promoting Ampathy with Nonfiction. English Journal, 101(6), 87-92. https://doi.org/10.58680/ej201220575

, , & (2011). Acoso escolar. Pediatría Atención Primaria, 13(52), 661-670. https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S1139-76322011000600016

, , , & (2022). Metodologías activas y TIC para prevenir el acoso escolar. Principales antecedentes de estudio y contribuciones. International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation (IJERI), 18, 151-169. https://doi.org/10.46661/ijeri.522

, & (2015). Selección de lecturas para la prevención del acoso escolar (bullying). Anuario de Investigación en Literatura Infantil y Juvenil, 13, 39-54.

, & (2016). ¿Leer para estar bien?: prácticas actuales y perspectivas sobre la biblioterapia como estrategia educativo-terapéutica. Investigación Bibliotecológica, 32(74), 171-192. https://doi.org/10.22201/iibi.24488321xe.2018.74.57918

, & (2012). “Everything...Affects Everything”: Promoting Critical Perspectives toward Bullying with “Thirteen Reasons Why”. English Journal, 101(6), 75-80. https://doi.org/10.58680/ej201220573

, & (2011). Revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis: bases conceptuales e interpretación. Revista Española de Cardiología, 64(8), 688-696. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.recesp.2011.03.029

, & (2012). El buscador BRAIN como herramienta al servicio del investigador. In Ponencias de la IV Jornada sobre buenas prácticas en el ámbito de las bibliotecas: Servicios de apoyo a la investigación en las bibliotecas universitarias (pp. 1-9). https://burjcdigital.urjc.es/bitstream/handle/10115/11511/BRAIN.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

, , , , & (2011). Strengthening Elementary School Bully Prevention with Bibliotherapy. Communique, 39(8), 12-14.

, , , , & (2005). Bibliotherapy: A Resource to Facilitate Emotional Healing and Growth. School Psychology International, 26, 563-580. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034305060792

, & (2017). La lectura en la salud y la enfermedad. Revista de Medicina y Cine, 13(2), 39-41.

, , & (2012). Beyond Bullying: Pairing Classics and Media Literacy. English Journal, 101(6), 56-63. https://doi.org/10.58680/ej201220570

, , & (2021). The Utility of Verbal Therapy for Pediatric Cancer Patients and Survivors: Expressive Writing, Video Narratives, and Bibliotherapy Exercises. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 9, 579003. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.579003

, & (2013). Reading Literary Fiction Improves Theory of Mind. Science, 342(6156), 377- 380. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1239918

(2012). Using Warriors Don’t Cry in a Capstone Project to Combat Bullying. English Journal, 101(6), 44-49. https://doi.org/10.58680/ej201220568

(2011). The Neural Bases of Social Cognition and Story Comprehension. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 103-134. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120709-145406

, , , , & (2012). Exploring Character through Narrative Drama, and Argument. English Journal, 101(6), 37-43. https://doi.org/10.58680/ej201220567

, , , & (2016). Actively caring to prevent bullying in an elementary school: Prompting and rewarding prosocial behavior. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 44(3), 164-176. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2016.1166809

Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional de España. (4 de noviembre de 2021). El Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional lanza una campaña de sensibilización contra el acoso escolar. https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/prensa/actualidad/2021/11/20211104-diaacosoescolar.html

, , & (2017). La biblioterapia como herramienta de ayuda aplicada en la biblioteca escolar: estudios de caso. E-Ciencias de la Información, 7(2), 19-43. https://dx.doi.org/10.15517/eci.v7i2.29259

, & (2007). Formulación de preguntas clínicas e introducción a la estrategia de búsqueda de información. In Atención Sanitaria Basada en la Evidencia. Su aplicación a la práctica clínica (pp. 47-71). Consejería de Sanidad de la Región de Murcia. https://www.murciasalud.es/recursos/ficheros/136606-capitulo_2.pdf

(2012). La empatía y su relación con el acoso escolar. REXE. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 11(22), 35-54

(1994). Bibliothérapie. Lire, c’est guérir. Éditions du Seuil.

, , , , , , , , , , , , , , , , .. & (2021). Declaración PRISMA 2020: una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Revista Española de Cardiología, 74(9), 790-799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.recesp.2021.06.016

Proyecto Biblioterapia (2018). Biblioterapia. Lecturas saludables. Xunta de Galicia.

(2013). Using YA Literature to Help Preservice Teachers Deal with Bullying and Suicide. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 56(6), 470-479. https://doi.org/10.1002/JAAL.168

, , , , & (2003). Using a novel unit to help understand and prevent bullying in schools. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 46(7), 582-591.

. (1 de febrero de 2022). Comparing the US and UK Education Systems. https://www.relocatemagazine.com/reeditor-09-d3-2015-7523-comparing-the-us-and-uk-education-systems

, , & (2022). Las Revisiones Sistemáticas y la Educación Basada en Evidencias. Espiral. Cuadernos del Profesorado, 15(30), 108-120. https://doi.org/10.25115/ecp.v15i30.7860

, & (2010). Revisiones sistemáticas y meta-análisis: Herramientas para la Práctica Profesional. Papeles del Psicólogo, 31(1), 7-17.

(Coord.) (2016). Yo a eso no juego. Bullying y ciberbullying en la infancia. Save the Children.

, & (2021). Escribir y comentar literatura en la red: el caso de la plataforma clubdeescritura.com. Espiral. Cuadernos del Profesorado, 14(29), 31-40. https://doi.org/10.25115/ecp.v14i29.4532

, , , , & (2018). Ideas for addressing electronic harassment among adolescents attending a video blogging convention. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 973. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5907-6

(2019). Healing Mental Health through Reading: Bibliotherapy. Psikiyatride Güncel Yaklaşımlar-Current Approaches in Psychiatry, 11(4), 483-495. https://doi.org/10.18863/pgy.474083

(2017). A Narrative Reflection on Examining Text and World for Social Justice: Combatting Bullying and Harassment with Shakespeare. Journal of Language and Literacy Education, 13(1), 1-14.

, & (1999). Bullies, Victims and Bystanders: A Method of In-School Intervention and possible Parental Contributions. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 30(1), 29-37. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1022619025074

(2013). Bibliotherapy and Bullying: Teaching Young Children to Utilize Peer Group Power to Combat Bullying. Theses and Dissertations, 3727. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/3727

, & (2015). Bullying Prevention in Middle Schools: A Collaborative Approach. Middle School Journal, 46(3), 25-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/00940771.2015.11461912

, & (2018). Bibliotherapy as a Strategy for Bullying Prevention. In J. U. Gordon (Ed.), Bullying Prevention and Intervention at School (pp. 37-52). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95414-1_3

UNESCO (2021). Más allá de los números: Poner fin a la violencia y el acoso en el ámbito escolar. Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura.

, , , , & (2020). La revisión sistemática y el metaanálisis como herramienta de apoyo para la clínica y la investigación. Revista Alergia México, 67(1), 62-72. https://doi.org/10.29262/ram.v67i1.733

, , , & (2015). The Bullying Literature Project: Using Children’s Literature to Promote Prosocial Behavior and Social-Emotional Outcomes Among Elementary School Students. Contemporary School Psychology, 19, 320–329. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-015-0064-8