Less than 5% of vertebrate genomes consist of gene coding sequences.

Moreover, the vast majority of these coding sequences are highly conserved

in all examined species. How did then morphological diversity arise during

evolution? The current genetic theory of morphological evolution states

that "form evolves largely by altering the expression of functionally

conserved proteins and that such changes occur through mutation in the

cis-regulatory sequences of pleiotropic developmental regulatory loci and

of the target genes within the vast networks they control" (Carroll,

2008). Therefore, to a great extent, evolution is the history of changing

the regulation of gene expression during development. Gene regulation is

not only crucial for development, but is also essential for controlling

cell physiology in adult organisms. Therefore, it is not surprising that

many of the large number of genome-wide association studies that have been

reported in the last few years indicate that the lesions associated with

human genetic diseases are usually not in the coding DNA of candidate

genes, but rather in the non-coding regulatory regions associated with

them (Maurano, 2012).

Less than 5% of vertebrate genomes consist of gene coding sequences.

Moreover, the vast majority of these coding sequences are highly conserved

in all examined species. How did then morphological diversity arise during

evolution? The current genetic theory of morphological evolution states

that "form evolves largely by altering the expression of functionally

conserved proteins and that such changes occur through mutation in the

cis-regulatory sequences of pleiotropic developmental regulatory loci and

of the target genes within the vast networks they control" (Carroll,

2008). Therefore, to a great extent, evolution is the history of changing

the regulation of gene expression during development. Gene regulation is

not only crucial for development, but is also essential for controlling

cell physiology in adult organisms. Therefore, it is not surprising that

many of the large number of genome-wide association studies that have been

reported in the last few years indicate that the lesions associated with

human genetic diseases are usually not in the coding DNA of candidate

genes, but rather in the non-coding regulatory regions associated with

them (Maurano, 2012).

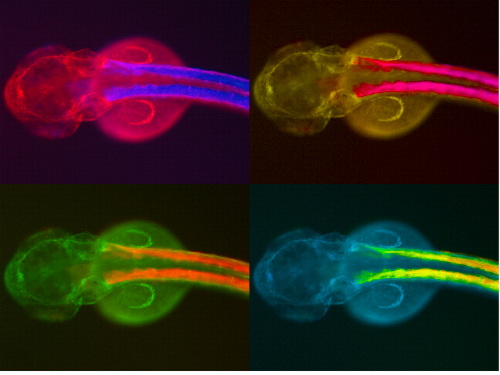

In our group we are combining epigenomics, chromosome capture assays, transgenic enhancer experiments and mutagenic studies to determine how cis-regulatory elements and chromatin structure contribute to development and evolution, and how alteration in this non-coding part of the genome affects human health.

Please visit the Research page for more information.

Please visit the Resources page for more information.